written by Corinna Kühnapfel

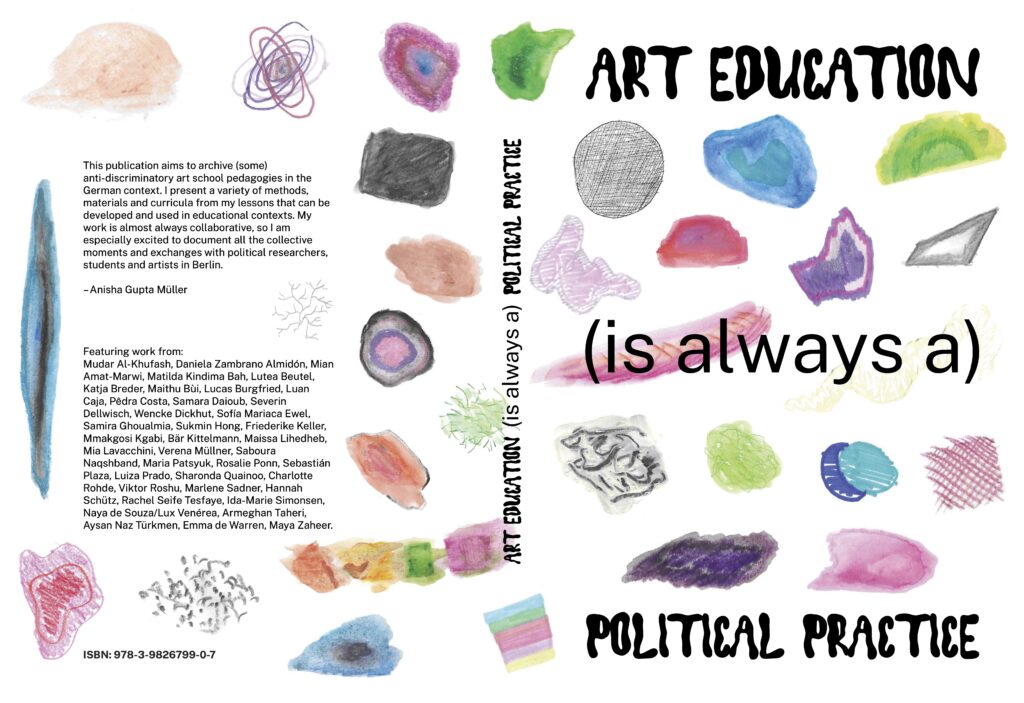

We are pleased to announce the publication of Art Education (is always a) Political Practice by Anisha Gupta Müller, a comprehensive exploration of anti-discriminatory pedagogies within the context of art education in Germany. This bilingual book (English and German) reflects on the author’s three years of work within the ARTIS project and includes essays, curricula, toolkits, and methodologies designed for educators interested in power-critical pedagogy. This is complemented by original artworks created by students, contributions from invited guests, and photographic documentation of the course.

Publisher: Berlin-Weißensee School of Art

ISBN: 978-3-9826799-0-7

Format: Softcover, ca.182 pages

Language: English, German

Publication date: December 13, 2024